Published June 2, 2023

Switzerland, for the 12th consecutive year, is ranked the most innovative economy in the world according to the Global Innovation Index 2022. It thereby outranks the United States, holding position two in the World Intellectual Property Organization’s annual global innovation ranking.

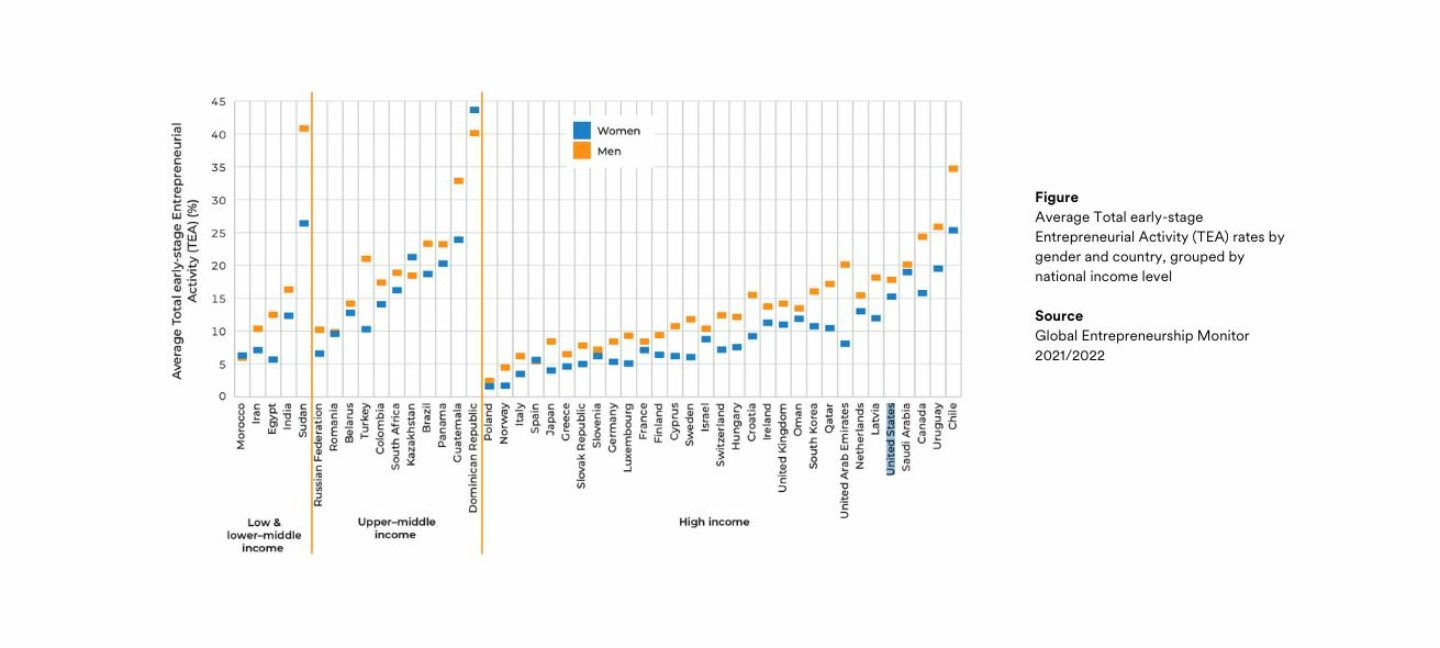

But despite its long history of innovation and entrepreneurship, Switzerland is struggling to keep up with the pace of startup growth seen in the US. This gap becomes even more apparent when comparing the percentages of female-founded startups in both countries. According to a 2021/2022 study conducted by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM), the total early-stage entrepreneurial activity (TEA) for women in the US responds to 15% in 2021, compared to 7.2% in Switzerland (see graphic). This corresponds to a TEA female-male ratio of 0.85 in the US and a wider gap of 0.58 in Switzerland.

According to the PitchBook-NVCA Venture Monitor 2020, the Bay Area remained the top region for female-led companies to raise money in the US. Bay Area based companies with all-female founder teams raised $5.8 billion of venture capital (2019-2023). In comparison, while the Swiss startup scene reached a record of CHF 3.1 billion in venture capital investments in 2021, the share allocated to female-led startups remained at only CHF 139.45 million.

The potential of Swiss female founders remains largely untapped due to cultural restraints toward entrepreneurship as well as limited access to funding and support systems, says Isabelle Siegrist, Founder and CEO of the Swiss startup incubator Sandborn.

According to Karine Wittmer, Vice President of Global Business Development & Innovation Programs at the Swiss Business Hub USA, Switzerland is currently experiencing a rise in programs supporting female entrepreneurs, which is encouraging. Nevertheless, when compared to the Bay Area, where this movement took root earlier, it becomes evident that Switzerland still has some ground to cover, she says. Interviews with several female founders, investors, consultants, and academics from both Switzerland and the Bay Area revealed insights about what needs to be done to step up the level of support for Swiss ‘fempreneurs’.

Why does Switzerland need more female inclusion?

Different perspectives accelerate innovation for a better future. More female-founded startups will increase diversity in organizational models as well as strategic goals that go beyond traditional goals like profit maximization, says Siegrist. Indeed, studies show that organizations with more female executives and board members perform better in terms of environmental impact and corporate social responsibility (CSR) goals.

With more female founders, there will also be a stronger focus on developing products that meet women’s needs, says Sophie Lamparter, Founder and Managing Partner at DART Labs. The Zurich and San Francisco-based incubator supports European health and climate-tech startups in entering the US market.

According to a 2019 Forbes article, 70-80% of all consumer purchasing decisions are driven by women. Having women’s perspectives in a team helps to make products more appealing to this significant consumer group, says Lamparter. Furthermore, according to a Fundera 2022 statistic, U.S. tech companies led by women generated 35% higher returns on investment than their male counterparts. Having a diverse team and investment portfolio, thus, proves to be a smart business move for companies and investors.

Cultural Attitudes towards Entrepreneurship

The high return on investment for female-led companies is partially explained by attitudes and perceptions toward entrepreneurship. According to a 2022 study by the Bern University of Applied Sciences, women tend to be perfectionistic and put greater emphasis on stability and financial security. While these traits are helpful in attaining profitability, they can pose obstacles when starting a business – a process that requires risk-taking, dynamic decision-making, and outside-the-box thinking, says Lamparter.

Several interviewees indicated that they observe women being more self-critical and tending to underestimate their own knowledge and abilities compared to men. They also see these characteristics being more pronounced in Switzerland compared to the Bay Area.

According to Wittmer, another challenge Switzerland is facing is that the so-called STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) subjects are not perceived as attractive by young women and a route to entrepreneurial careers.

Caroline Matteucci, Founder of Swiss AI-startup Cryfe, furthermore highlighted the prevailing skepticism towards the compatibility of entrepreneurship and motherhood. Considerations of family responsibilities and work-life balance profoundly influence women’s career choices, says the established mompreneur.

Support Systems

As Wittmer says, efforts are being made to develop more inclusive and tailored programs that address the specific needs and challenges faced by women founders in Switzerland. A challenge, however, remains the limited awareness about and accessibility to such support programs, states Matteucci.

In an effort to make available programs and resources more visible, the Female Founders Initiative provides an overview of organizations that play a vital role in the Swiss startup ecosystem and assist women in their entrepreneurial journey. Despite the gradual increase in tailor-made programs, interviewees stressed that women continue to have fewer relevant networks and mentorship opportunities than are available to men.

Added to this, many of the existing programs focus on deep-tech and science-backed innovations. While it is true that there is an increasing number of female-founded IT/AI/Software, Biotech/Healthtech, and Fintech startups, the Swiss Female Founders Map shows that the majority of female-led startups can still be found in the fields of Consulting, Social Impact, Healthcare/Fitness/Wellness, and Fashion. These startups are not necessarily tech or science-based and thus not eligible for those initiatives. Hence, they miss out on the support, visibility, and recognition that tends to come with the nomination for and participation in such programs.

Siegrist says that the Swiss startup ecosystem provides solid support for female founders who are in the early stages of their entrepreneurial journey; The Swiss commercial register and initial support programs report close to equal participation of women and men. However, in the more advanced entrepreneurial stages, such as fundraising for growth and scale, the support landscape becomes scarcer, the hurdles more challenging, and unequal representation more pronounced.

Access to Funding

Early-stage startups usually have two to three co-founders by the time they start pitching to venture capital firms (VCs), says Lindsey Mignano Co-Founder at SSM, a boutique women-owned corporate law firm. According to the Bay Area-based lawyer, VCs recognize that having women at the top level of organizations not only increases diversity but makes teams more effective and efficient, so they welcome gender diversity in the C-Suite. Where we are still seeing struggles statistically is with the all-female founder teams or the solo female founder team.

According to the Swiss Startup Radar 2020/2021, a report conducted by the Swiss startup news channel Startupticker, investment in women-led startups in Switzerland is, on average, 33.33% lower than that in male-run startups. While companies with a female CEO accounted for almost 7% of financing rounds between 2012 and 2020, they only received 4% of the total capital.

Anne Cocquyt is the Founder and CEO of The GUILD, a global community of female entrepreneurs and investors. She runs an advisory firm that helps startup founders with their next fundraising round and helps VC funds and accelerators combat gender bias. Her goal is to change the negative effect of gender biases on investment in female founders, which according to her, is most severe in later-stage funding rounds (Series A) where the investment tickets are larger (above $6 million).

Mignano observes this too in her practice and says that female founder clients of SSM may spend double the time to raise half the money that men do because they struggle to find VC and partnership contacts to raise capital and deploy their technology, spend more time on developing their product or services before going to market, and on top of that, experience more rejection at the financing stage.

She attributes this to the fact that female founder clients of hers don’t inherently have the professional network that many male founders have, especially when those female founders didn’t graduate from top business schools or STEM programs. This is crucial because VC leadership is still overrepresented by white and South Asian men, and unconscious biases are at work. Sympathies and empathy matter, confirms Cocquyt, who is familiar with the founder and investor sides. While having more female founders who develop products for women’s needs is beneficial, pitching those products to men, who don’t know the market for those products, is less so, she explains.

«Women need to prove more than men to receive funding – they basically need to overperform.» – Sophie Lamparter

As investors generally perceive the high-risk affinity of entrepreneurs as a potential for high returns, female (presumably risk-averse) founders may be seen as less favorable to invest in. It is also a reality that women receive different questions from investors than men. Women get tested for their knowledge and qualifications or receive discretely framed questions about their family planning, whereas men get to talk about the growth potential of their startups, says Lamparter. However, we can’t just blame men, says Siegrist and stresses that women also tend to underestimate and set higher requirements for women.

«Parts of the venture capital industry make investing in female startups feel like half-investment, half-charity.» – Sophie Lamparter

There’s an additional hurdle created by a seemingly positive trend: female investors investing in female founders. One of the characteristics of startups founded by women is that they are more likely to be supported by female investors in their early funding rounds. However, this characteristic becomes a disadvantage when scaling up. As an article by Harvard Business Review shows, founders are less likely to receive additional funding in a later funding round if the previous investors are women. This roots in the assumption that the investment was motivated by the goodwill of women supporting women rather than the true potential of the startup and its founder. Early female VC can thus hinder growth capital needed to scale up.

«Investors are going to go with the company that has bigger growth projections.» – Anne Cocquyt

The hurdle to receiving necessary funding is further heightened by the type of businesses women are more likely to run. According to Cocquyt, many women start businesses that are not that growth-driven, which is not a bad thing but might not fit the traditional venture model that well.

If women build consumer products and goods (CPGs) tailored towards women’s interests, male investors with check-writing power may struggle to understand product market fit, scalability, or other key investment metrics. They may be more hesitant to invest as a result, says Mignano.

«There’s a lot of macroeconomics and patriarchy at work.» – Lindsey Mignano

The biggest checks have historically gone to hard-sciences like medtech, biotech, or lifesciences. Those are the hot industries with high growth potential, explains Siegrist. But there’s a pipeline issue. You need experience to build a startup in this field. And for this case, doing the math is fairly easy. If there are not more women with knowledge in STEM, there won’t be more female founders in those industries.

«Women can self-select what field they want to go into. However, our choices are informed by the patriarchy. We’re socializing people into these interests. It starts at a very young age, and that’s why it is a macro issue», explains Mignano.

What can Switzerland learn from the Bay Area Entrepreneurship Ecosystem?

In the Bay Area, there is a higher awareness of the underrepresentation and the diversity of women, says Wittmer and stresses that the promotion of female entrepreneurship in Switzerland must be fostered from the academic side, starting early on in young people’s education.

Most startups in Switzerland are university spin-offs and as such, benefit from easier access to funding and support, says Carole Ackermann, Founder of the VC firm Diamondscull and Senior Lecturer at the University of St. Gallen (HSG). According to the Federal Statistical Office, the female participation rate in technical sciences in Switzerland is only 32% (2019). In comparison, for the US, the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) reports that women represent 45% (2020) of students majoring in STEM fields. It is thus crucial that Swiss universities enhance their efforts to increase female representation in Business and STEM, subjects that are likely to spawn female founders. Higher representation of women in those programs will gradually lead to a change in mindset and more diversity, concludes Ackermann.

Moreover, Swiss universities should further strengthen the provision of resources for women, such as classes in technology from an entrepreneurial approach, connections to investors, or mentoring and guidance, says Ackermann.

Victoria Woo is the Director of INSEAD San Francisco Hub for Business Innovation and a lecturer at Stanford University and Presidio Graduate School. As an executive educator and founder of five startups herself, she emphasizes the need for a reasonable and reliable childcare system. Ackermann also highlights that affordable childcare and reliefs in the Swiss tax system would make it more worthwhile for women to increase their work pensum.

An initiative exemplifying the Bay Area’s unique approach to assisting female professionals comes from the State of California. Pursuant to Labor Code Section 1030 every employer is required to provide reasonable break time and adequate space for women to breastfeed their children.

But there are more examples of how the public sector can initiate change. In its efforts to support America’s small businesses, the Biden Administration announced to expand the Women Business Centers network to 160 centers across the country. Those centers aim to assist women entrepreneurs through training, mentoring, business development, and financing opportunities.

Cocquyt started her first business in the Bay Area 12 years ago. Back then it was very male-centric, but there was a support system for female founders she says. You could go to events almost every night to learn new things, pitch your idea, and meet people that potentially help you go forward. Since then, a lot of diversity-promoting funds and organizations have popped up, such as the Women in Technology Network, the Female Founders Initiative, and Forerunner Ventures. To help women navigate through this increasingly complex landscape, Cocquyt is undertaking efforts to create a map that will help female founders find the resources they need.

«Of course, in an ideal world, we do not need exclusive female funds and programs to address the gender investment gap and foster diversity within startup teams. In reality, however, these funds are needed to accelerate change.» – Isabelle Siegrist

Consultancies and incubators, like the ones founded and run by the established women who contributed to this article, teach women the necessary skills to successfully pitch their ideas to investors. Siegrist emphasizes that Switzerland needs more bootcamps and mentoring programs that teach hard skills to female founders and expose them to people that have done it before.

She elaborates, that these programs need to promote mixed founder teams and ensure that they have a balanced slate of participants as well as sufficient women experts from different industries that can act as role models and mentors. Woo sees the importance of those considerations too, which is why, when hosting events at the INSEAD hub, she always sets herself the expectation to have a balance of women and men on the panel. Otherwise, it would just be a manel, she says.

Furthermore, Siegrist stresses that support programs need to consider that their participants have to balance work-life responsibilities and create sufficient flexibility or support to help women manage this double burden. Lastly, they have to broaden their understanding of innovation to become better accessible to a large proportion of female founders.

Having founded a startup without the support university spin-offs receive, Matteucci stresses the need to increase the level of support for non-university spin-offs as well as non-scienced-backed startups. Swiss support programs have to broaden their understanding of innovation to become better accessible to a large proportion of female founders, she says.

In addition to funds and programs tailored to women, there is also a need for more women in VCs, networking opportunities, and visibility for female role models.

«I firmly believe that as more women matriculate into leadership in venture firms, the amount of funding appointed to female founders will increase.» – Lindsey Mignano

Cocquyt suggests that VCs should set a quota for themselves and try to find new ways to attract female associates and partners. If there’s just one woman on the board, she will be an outsider. But as soon as you have two or more women on board, the dynamics are going to change massively. That’s what we need to aim for, says the fempreneur and author.

To address the gender gap in Swiss VCs, Mignano recommends offering internship programs specially designed for female students as California-based women-owned VCs have been able to attract women and minorities through such initiatives. Siegrist also sees great potential in such programs, as many internships in Swiss VCs go away privately.

In light of this, networking opportunities for women are invaluable. While Switzerland has seen a rise in associations that offer such platforms – examples are femella – Women of Tomorrow, FEM’UP Switzerland, or Universa – there needs to be more of those initiatives and more visibility.

«Creating an inclusive environment for female founders greatly benefits from the active participation and support of men as well» – Karine Wittmer

Drawing from her professional experience in connecting education and businesses, Woo states that the goal of any program and organization must be to get men and women involved and sensitized to gender biases. Cocquyt adds that especially male investors, who are still the vast majority in VCs, should evaluate and question their own biases when female founders ask for money. Moreover, they should reach out to women’s organizations, partner up with them, participate in their events and programs, and help fund them.

According to Wittmer, the Bay Area is well ahead when it comes to men’s recognition and support of female entrepreneurship. Indeed, there’s such a progressive mindset in the Bay Area that a very traditional or biased male would likely get trampled upon, states Woo.

What should we take away from all of this?

Many of the challenges female founders face are present in the Bay Area as well as in Switzerland. Both regions are increasingly equipped to foster female founders through initiatives such as incubators or daycare centers. According to Lamparter, the difference is mainly that this supportive ecosystem is more advanced, and its use is more accepted for women in the Bay Area.

As Mignano says, «funding is a major reason to come to the Bay Area, because obviously, capital is here. But the Bay Area stands out because everyone is incredibly encouraging about women in venture and women in startups. Doing risky, brave things and having that met with enthusiasm and applause – even if it fails – you can’t find that anywhere else».

«If we don’t talk about failure, we are depriving ourselves of learning from our mistakes» – Victoria Woo

Woo emphasizes the importance of fostering a culture where people talk about their failures and perceive is as part of their growth process. Failure should not stop us from trying again and again.

So, whether you want to become a fempreneur or implement reforms in policy, academia, or VC, here are two important Bay Area lessons for you: Yes, go do it! And please, think big!

Edited and written by Sophia Burri (Communications Associate at Swissnex in San Francisco)

Input by Karine Wittmer (Vice President of Global Business Development & Innovation Programs at the Swiss Business Hub USA), Sophie Lamparter (Founder and Managing Partner at DART Labs), Isabelle Siegrist (Founder and CEO at Sandborn), Caroline Matteucci (Founder of Cryfe), Lindsey Mignano (Co-Founder at SSM), Anne Cocquyt (Founder and CEO at The GUILD), Carole Ackermann (Founder of Diamonscull), and Victoria Woo (Director of INSEAD Hub San Francisco)