Over the past weeks and months, we have all learned how distance and lack of proximity with one another impact our lives, our relationships, our children’s schooling, and our work. We are continuing to learn — both as individuals and as a society — what it means to be alone. Throughout this period of isolation, we have also been challenged to experiment with new, socially distanced ways of connecting and interacting with one another.

While all of us at Swissnex in Boston and New York have embraced various online webinar and conferencing tools, you may have noticed that over the past month we also did some experimenting with creating new forms of human connections – via robots. We would like to share some of what we’ve learned from our programming around the virtual robotic installation “Handshake,” particularly in regards to human-robot interaction and how art and design can contribute to shaping the future of robotics.

For an exclusive behind-the-scenes look at Handshake, take a listen to our podcast episode featuring AATB and experts in robotics from leading Swiss and US institutions.

Robots and Effective Collaboration

By now most of us have experienced automated check-in systems at airports and have read about postal deliveries soon to be executed by autonomous vehicles. Robots are blending into our lives, and in the face of this global pandemic, they have presented us with interactive means of connecting with one another. The most effective way to create connection, familiarity, and establish a joint sense of purpose is by creating something new together.

This is not only true for collaboration between humans but also between humans and robots. This is why Professor Masahiko Inami from the University of Tokyo has focused on developing robots for remote collaboration between humans. In his project FUSION, he enables us to actually learn from one another and physically work together across large distances by physically interacting with a robotic arm that is remotely steered by someone else.

When it comes to places humans can’t ordinarily get to, Professor Roland Siegwart from ETH Zurich has us covered. He has been exploring the potential of robotics in the field of telepresence and automation for over 30 years now and is a pioneer in the development of drones and autonomous flying robots. According to Siegwart, moving beyond AR/VR technologies and combining them with robotics will “introduce more new and physically augmented forms of telepresence very soon.”

Siegwart is working towards a future where highly specialized robots engage in physically demanding and dangerous tasks in industries such as mining or firefighting — taking humans out of unnecessarily risky environments. But of course, that future will not happen overnight, giving high-risk industries and professions time to adapt to working with robots. Siegwart explains that because robots are extremely complex machines, the transition to increased robotics will likely be a steady evolution, as opposed to the dystopian and abrupt advances that pop culture likes to imagine.

Humans can actually use automation to do even more, or move on to new jobs.

So robots aren’t about to take over the world, but in a lot of ways, we are already surrounded by robots, as NASA’s Steve Rader points out. “In our everyday lives, people are interacting with a Google Home or Alexa or in the grocery store, they’re checking out with a robotic cashier, or they’re tripping over their robotic vacuum cleaner. Robotics is much more a part of our lives now,” he says. And for Rader, that’s not a bad thing. “Technology, in general, is extending what humans can do. And robotics is a very specific piece of that, that is actually moving humanity towards more capability. Humans can actually use automation to do even more, or move on to new jobs,” he says. In other words, robots can help us say goodbye to uninspiring and meaningless tasks, and open the door to a plethora of jobs and tasks that are more engaging and complex.

Prof. Jamie Paik of the Reconfigurable Robotics Lab (RRL) at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (EPFL), argues that the potential for the future of robots lies in their physicality. Our physical interaction and connection with the world around us is and remains very important. “After exploring augmented reality, we are heading towards tangible reality,” says Paik. We are still missing a smooth integration of feeling, or haptic feedback, in technologies enabling human-to-human interaction via human to robot interaction.

Paik asks us to imagine how much more we can achieve in telepresence and remote collaboration — in space exploration or surgery on the human body for example — if you can actually achieve haptic feedback from robots. Will advances in haptic feedback and robotics ever really be able to replace the need for human-to-human interaction? Paik doesn’t think so. “Any extra physical queue will enhance our remote interaction. Robotics will never replace human-to-human interaction but will enhance it when feedback mechanisms are optimized,” she notes. You can watch Paik’s Ted Talk on her versatile origami robots and how they recreate the sensation of the human touch for optimal interactions.

Creating Empathy with Robots

You can’t replace human-to-human interaction. But, according to Andra Keay, Managing Director at Silicon Valley Robotics, that does not mean you cannot achieve intimacy or emotion through the use of technology. She points out that the COVID-19 crisis has forced us to communicate in “some very intimate and emotional situations” — such as connecting with loved ones, celebrating birthdays, or attending funerals — “and we’ve realized that we would rather have that than no communication.” For Keay, empathy is something we can incorporate into our technologies. “I think we can do a lot in the future for actually providing emotional care for people through robot technologies,” she says.

When collaborating with humans, we agree that it is not ethical to treat others as a means to our own ends — using a person as if they were an object erodes our own humanity. Does using a robot in that manner have the same effect? Will it enhance our own pre-existing biases? Keay raises some of these concerns when talking about the decisions we make about how and to what end we design robots. As Jonah Engel Bromwich argues in a New York Times article about aggression towards robots, our tendency to dehumanize robots paradoxically comes from the instinct to anthropomorphize them.

Robotics Research Specialist at the MIT Media Lab, Kate Darling writes and talks about how we empathize with robots and the importance design has in this context. She argues that it might be useful to move away from designing robots in the likeness of humans since this can lead to false expectations and may lead to adverse effects on how we interact with humans. Rather, she proposes basing robotic design on the relationship between humans and animals, enabling us to relate with robots as a separate form of intelligence but not losing our capability to empathize with them. She discusses this approach in her forthcoming book titled “The New Breed: What our History with Animals Reveals About Our Future With Machines.”

When Artists Use Robots

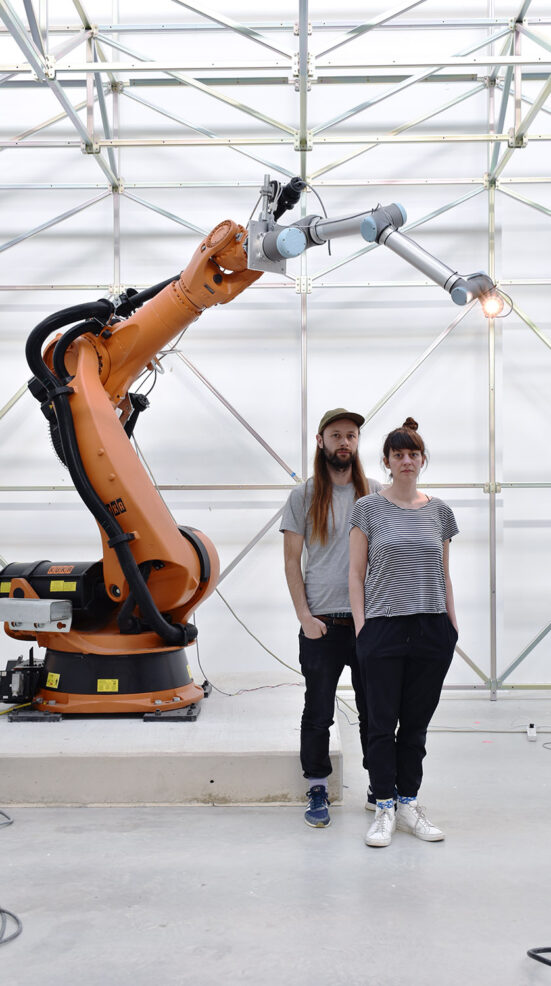

Design affects the way we relate with and ultimately how effectively we collaborate with robots. Giving designers a seat at the table when robotic systems are developed might also change which problems are tackled through robotics in the first place. The Swiss design duo AATB sees their role as just that. Through their artistic non-industrial robotic installations, AATB raises questions around who robots are developed for and by, and what applications could bring them further.

Artist Stephanie Dinkins, who recently did a residency at the art and technology center Eyebeam, a close partner and collaborator with Swissnex in Boston, exemplifies how deep questions around AI and robotics can be addressed through art. Her recent work, “Conversations with Bina48” explores whether an artist and a social robot can build a relationship over time. It is based on emotional interaction and potentially reveals important aspects of human-robot interaction and the human condition.

Thus far Dinkins and her robot Bina48 have discussed family, racism, faith, robot civil rights, loneliness, knowledge, and Bina48’s concern for her robot friend that are treated more like lab rats than people. This brings us back to the ethics of humanoid design for robots and the important questions around which humans robots are built.

At Swissnex, we believe that an artist’s or designer’s perspective on traditionally scientific topics such as robotics is an invaluable asset. Neither AATB nor Stephanie Dinkins are trained roboticists. They are artists who work with robots through experimentation and collaboration, and a do-it-yourself approach. Through their curiosity and playful experimentation, they are diversifying the players shaping how we interact with robots in the future.

The duo is wrapping up their latest work, an interactive robotic installation titled ‘Handshake’, which can be experienced online until midnight tonight (EST), June 30th. Over the course of the past month, this installation has enabled more than 3000 people from around the globe to virtually touch one another via two robotic arms with gigantic hands that physically move to touch one another in AATB’s studio in Marseilles.

Hear the story behind Handshake

Want to listen to AATB and some of the experts featured in this article talk about robotics and human interaction? Take a listen to our podcast episode, available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.