The epidemic of the coronavirus challenges the thought process and practice of architecture and urbanism in the sense that it suggests new opportunities for the cities for healthcare and epidemic prevention. In Brazil, Covid-19 revealed the social inequalities, so present in the favelas and periphery, especially with respect to the Black population who historically occupies these territories. Brazil, and more precisely Rio de Janeiro, set records for tuberculosis cases in Latin America because of a lack of attention of the State to this share of the population.

Our public health system, which in a recent past managed to be considered a global reference, was already put under pressure by diseases such as hepatitis, anaemia, measles and tuberculosis – among others – because of lack of investments. The large deficit in universal access to water and wastewater treatment also show the big challenge of the XXI century, in which access to treated water is a main measure in the fight against the coronavirus and on a sanitary justice agenda.

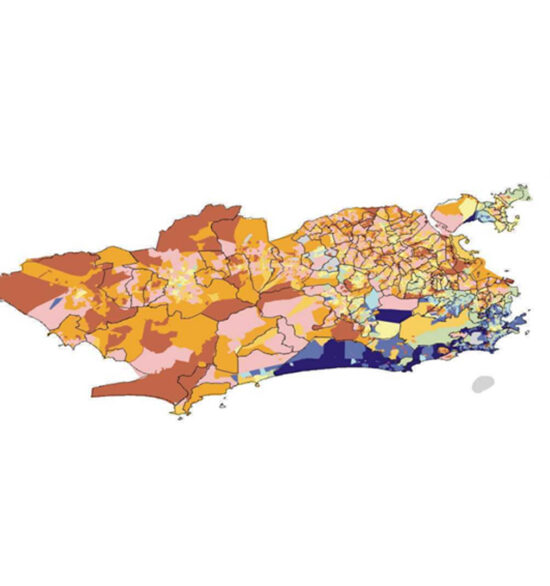

South-eastern Brazil concentrates most of the network of water sanitation and even so, shows discontinuities in the access to basic sanitation within its territory (see the map above, from 2010).

This and other diseases related to the lack of access to basic sanitation and the habitational precariousness for example, are responsible for high mortality levels of people in vulnerable social positions, especially Black people. The scenario observed in the city of Rio de Janeiro is a portrait of the rest of Brazil, in terms of lack of access to water, healthcare facilities and decent housing.

Brazil who was, until little less than 10 years, the seventh world economy is today one of the most unequal countries in the world, with chronical problems comparable, in terms of numbers, peripheries of the large conurbations of favelas in sub-Saharan Africa.

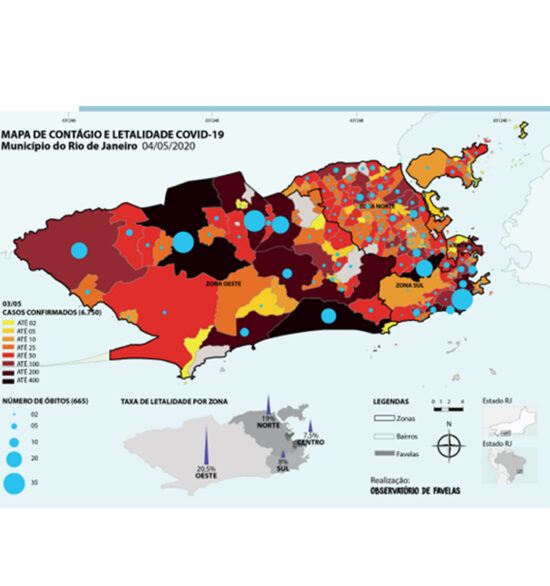

Map 2

Income and racial distribution in the municipality of Rio de Janeiro, constructed with ARCGIS, using IBGE Census of 2010.

On the map depicted above, we can see the high concentration of income and white people in the noble areas of Rio de Janeiro (in blue). If we compare the distribution of health equipment to the rest of the municipality, we can understand this unequal distribution of income and race on the territory structures the inequality.

Map 3

Contagion, deaths and mortality of Covid-19 in the Rio de Janeiro Municipality.

Observing the map of the infection distribution, death and mortality rate of Covid-19 in Rio de Janeiro, we can see that despite the contagion having started in the South Zone of the city (Zona Sul, with high income), the most affected neighbourhoods, in terms of number of cases, are those with less income, and more Black people. By the time of the preparation of this article, the mortality rate in the Zona Sul was 5%, whereas a favela in Campo Grande had a rate of 26.9%.

When looking at the measures to combat Covid-19, in Brazil and other places around the world, irregularities in the mitigation and control policies can be observed, as well as conflicting policies. Throughout the epidemic there have been 7 municipal decrees on rules regarding Covid-19, and 4 state decrees, with sanitary and urbanistic rules, conflicting the municipal rules.

In this sense, local actions in the crisis management are fundamental in order to control the spread of the virus in the favelas and precarious settlements, considering the importance of the local governance for the construction of an agenda focused on territorial actions.

For this article, the initiatives of the communities of Paraisopolis, Rocinha, Alemão, Xicheng, City of God and Providencia have been compared, and the following measures have been identified repeatedly:

– Local combat to the Covid-19 and urban problems

– Local counting and monitoring of cases

– Localisation and support to the most vulnerable

– Block-level data

– Popular self-organisation

– Private financing

Measures that were repeated in Paraisopolis and Xicheng:

– Public healthcare workers

– Coordination with public spaces and equipment (schools, churches, parking lots and local healthcare facilities)

– Construction of community cabinets open to the public

In this sense, in a post-epidemic scenario, it is important to understand the principal factors of urban inequality, constructing social technologies able to face future inequalities. Access to housing, access to urban territory, an equal distribution of equipment, the elimination of the urban expulsion of poor and Black people from places with infrastructure, all of these must be put on the post-Covid-19 agenda, or we wouldn’t have learned from the sanitary crisis.

It is necessary to tackle the crisis raising questions on the hyper concentration of poor people in the urban centres, on the construction of new development and resource management support mechanisms that won’t harm the environment and preserve water reserves. A renegotiation of the productive capital and labour relations needs to be made, in which it is important to build an alternative agenda to capitalism and work itself, in light of the overload of tasks and the inefficiency of rentier capital to generate neither a full-employment situation nor a social welfare agenda.

With this, it is important to ask a question that will conclude this article and begins a new urgent discussion: are we merely building a post-epidemic agenda or a post-capitalism agenda? This is a fundamental question for what is yet to come.