Current State of Sustainable Architecture in China

Sustainable architecture refers to the design and construction of buildings that prioritize environmental stewardship, resource efficiency, and occupant well-being. In recent years, China has made significant strides in this area, driven by government policies and a growing awareness of environmental issues. The Chinese government has implemented initiatives to promote sustainable building practices, including the “Green Building Action Plan” (2020), which aims to increase the proportion of green buildings in urban areas.

Notable examples of sustainable architecture in China include the Tianjin Eco-City, a collaborative project between the Chinese and Singaporean governments, which aims to create a model for sustainable urban living. Other key projects include the Shanghai Tower, featuring a double-skin facade for energy efficiency, and the Beijing Daxing International Airport, designed with sustainability in mind. These projects serve as important case studies for future developments.

On the standard level, China has developed several national standards on sustainable building, such as the Green Building Standard and the Nearly Zero Energy Building Standard. Recently, there has been a shift in focus from energy consumption to carbon footprint, leading to the drafting of the Zero Carbon Building Standard, developed in collaboration with the Sino-Swiss Zero-Emission-Building Project. Given China’s four distinct climate zones, the methods for achieving zero carbon buildings are left to provincial authorities, who are responsible for detailed regulations tailored to local conditions. However, current standards primarily focus on the operational phase of buildings and have not yet comprehensively addressed the manufacturing phase of building materials, construction practices, and disposal.

Certain types of renewable energy, such as geothermal energy and the thermal use of river, lake, and underground water, face limitations in China due to a lack of reliable data, concerns about environmental impact, and higher investment costs. In contrast, photovoltaic technology, combined with battery storage, is more suitable for the country. China is also exploring ways to leverage the potential of batteries from popular electric vehicles (EVs) at the regulatory level. Collectively, these technologies and strategies are referred to as PEDF (Photovoltaic, Energy Storage, Direct Current, Flexibility).

Despite these advancements, challenges remain. Rapid urbanization, population growth, and economic pressures often lead to compromises in sustainability. The fast-paced development of urban areas frequently prioritizes immediate economic gains over long-term sustainability. Additionally, there is a lack of comprehensive regulations for sustainable construction, resulting in inconsistencies in implementation.

Circular Construction in China

Circular construction emphasizes the reuse and recycling of materials, minimizing waste, and creating closed-loop systems within the built environment. The transition towards a circular economy in China is gaining momentum, supported by the “Circular Economy Promotion Law,” enacted in 2009, which encourages resource efficiency and waste reduction across various sectors, including construction.

In 2024, a state-owned company, the China Resources Recycling Group, was established in Tianjin Eco-City, focusing on circular economy initiatives in industrial production, including metals, plastics, and petroleum. This initiative is part of a broader effort to integrate circular economy principles into the fabric of China’s economic development. Additionally, “Waste-to-Energy” inceneration plants that convert municipal solid waste into energy contribute to circularity by providing electricity and reducing landfill waste.

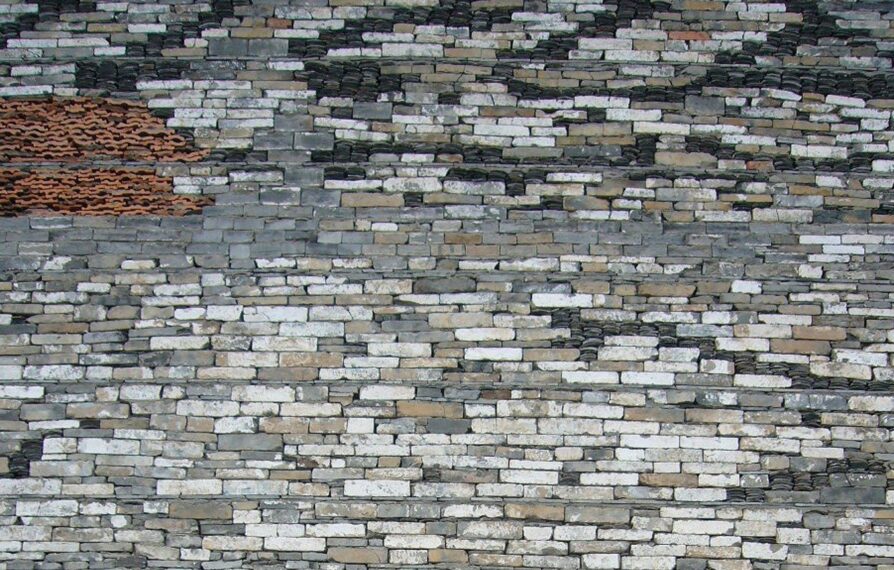

Examples of circular construction in China include the use of recycled materials in building projects, such as reclaimed bricks. The works of architect Wang Shu, winner of the Pritzker Prize, exemplify this approach. He reuses old bricks, roof tiles, and pavements from demolished traditional houses in their new projects, emphasizing not only the historical context of Chinese cities but also critiquing the “Tabula Rasa” strategy of urbanization. Their work advocates for a more sustainable approach to modernization in China.

Five Scattered Houses, Photo © Lang Shuilong

Recycled bricks and roof tiles on façade , Photo © Lv Hengzhong

In rebuilding Wenchuan after the 2009 earthquake, Chengdu architect Liu Jiakun introduced “rebirth bricks,” made from recycled debris and reinforced with chopped wheat branches from local villages. This lightweight material is produced using a semi-manual tool common in local craftsmanship. Liu’s approach symbolizes both physical and spiritual renewal, transforming destruction into a foundation for hope with the idea of circular construction. In rural areas, valuable old building elements such as windows, doors, and bricks are carefully salvaged and resold for new construction, especially those with traditional craftsmanship.

Liu Jiakun on rescue work after earthquake 2009, , Photo ©Jiakun Architects

Rebirth Bricks, Photo ©Jiakun Architects

Shuijingfang Museum, Photo ©Jiakun Architects

However, the adoption of circular construction practices remains limited in scale and faces several barriers. These include a lack of awareness and understanding of circular principles among industry stakeholders, as well as limited access to technology and funding. Furthermore, many Chinese citizens are influenced by a progressive mindset that values new materials and constructions over reused or recycled ones, which hampers market acceptance of circular practices. The perception that “new is better than old” can lead to resistance against innovative construction practices that prioritize sustainability.

Comparative Analysis: China vs. Switzerland and Other European Countries

While both China and Switzerland are advancing toward sustainable architecture and circular construction, their approaches differ significantly. In Switzerland, sustainable architecture is deeply ingrained in the cultural fabric and its specific climate condition, emphasizing high-performance insulation, energy efficiency, and environmental responsibility. Swiss building codes promote the use of renewable energy and sustainable materials throughout a building’s life cycle.

The Swiss approach is holistic, integrating architectural design with low-tech solutions. For example, renowned architects Herzog & de Meuron are planning a zero-emission office building called HORTUS (House Of Research Technology Utopia Sustainability) in Allschwil near Basel, focusing on the whole life cycle carbon footprint and aiming to decarbonize the project through a holistic design method tailored to the specific site and function. Moreover, nearly all open architecture competitions in Switzerland emphasize the importance of sustainability at every level, leading to a new aesthetic perspective on architecture itself.

HORTUS Basel, Photos ©Herzog de Meuron

HORTUS Basel, Photos ©Herzog de Meuron

HORTUS Basel, Photos ©Herzog de Meuron

European countries like Germany and Sweden also showcase robust sustainable building practices, with a focus on community involvement and innovation. Germany’s “Passivhaus” standard emphasizes ultra-low energy consumption, while Sweden’s commitment to timber construction aligns with its sustainability goals. However, in China, timber construction remains restricted due to material shortages and associations with ecological destruction. The awareness and availability of timber materials need to be updated to meet the new challenges posed by global climate crises and carbon neutrality goals.

In contrast, China’s approach is often more top-down, driven by government policies and initiatives. While this has led to rapid advancements in sustainable building, it can sometimes result in a lack of grassroots engagement and public awareness. For many projects in China, sustainability is often regarded as a technical solution managed by HVAC engineers or energy consultants, with less emphasis on architectural design aspects. This can lead to buildings that meet technical standards but lack the integration of sustainability into the overall design philosophy.

Cultural attitudes play a significant role in shaping approaches to sustainable architecture and circular construction. In Switzerland, sustainability is often viewed as a collective responsibility, with strong community engagement in planning and decision-making processes. Citizens are more likely to support sustainable initiatives, influenced by a cultural appreciation for nature and environmental conservation. In contrast, rapid urbanization and economic growth in China have often overshadowed environmental considerations, highlighting the need for greater public education and engagement on sustainability issues.

Despite the long-term benefits of sustainability, which can take one to two decades to yield returns, many in China are particularly sensitive to initial investment costs due to its developing status compared to European countries. Energy prices in China are lower, as the government views them as part of public service; thus, end users, such as citizens and factories, tend to care less about operational costs and more about investment costs. This sensitivity has become even more pronounced in recent years amid the ongoing real estate crisis.

Furthermore, cultural practices regarding comfort and building usage are significant. Unlike the 24-hour climate-controlled buildings in Switzerland, most buildings in southern China are only heated during winter or cooled during summer operational hours. It’s common for office workers in China to wear jackets or sweaters while working in winter. While this approach helps maintain relatively low overall energy consumption per person, it leads to inefficient heating and cooling due to a reliance on air conditioning technology and unclear insulation boundaries within buildings and rooms.

Innovative Approaches for Transition to Circular Economy

Emerging technologies play a vital role in promoting sustainable architecture and circular construction in both China and Switzerland. Swiss interdisciplinary planning methods can assist China in developing comprehensive sustainability solutions. Additionally, Swiss startups are at the forefront of innovations in sustainable materials aligned with circular economy principles, gaining recognition in both local and international markets. Switzerland’s experience with retrofit projects can also aid China in enhancing the sustainability and quality of life of its existing buildings, many of which were constructed with insufficient attention to sustainable practices. Collaborative initiatives between Swiss and Chinese organizations, including research partnerships and technology exchanges, are essential for fostering innovation and sharing best practices.

Education and training are crucial for fostering innovation, and institutions in both China and Switzerland are increasingly emphasizing sustainable design and circular economy principles. The “10-R strategy” (R0: Refuse, R1: Rethink, R2: Reduce, R3: Reuse, R4: Repair, R5: Refurbish, R6: Remanufacture, R7: Repurpose, R8: Recycle, R9: Recover) needs greater attention in China and should become a popular lifestyle, particularly among the younger generation. Notably, Swiss universities of applied sciences (German: Fachhochschule) could play a significant role in assisting Chinese vocational colleges by providing training for skilled workers and managers in construction, as well as for facility managers focused on building operations and maintenance. By equipping the next generation with the knowledge and skills to implement sustainable practices, both countries can work towards a more sustainable future for the built environment.

Future Outlook

Driven by the government’s commitment to carbon neutrality by 2060, the future of sustainable architecture and circular construction in China appears promising. Growing awareness among consumers and industry stakeholders will foster a more conducive environment for innovation. Collaboration between Switzerland and China presents significant opportunities, leveraging Switzerland’s expertise in sustainable design and China’s rapid urbanization.

As global climate policies become stricter, the pressure on both countries to adopt sustainable practices will intensify, acting as a catalyst for innovation and collaboration. Integration of sustainability into economic planning and development strategies will be essential, with policymakers in China prioritizing sustainable practices in urban planning and infrastructure development.

In conclusion, sustainable architecture and circular construction are critical in addressing the environmental challenges facing our world today. While China has made significant progress, challenges remain. The comparative analysis with Switzerland and other European countries highlights the similarities and differences in approaches, regulatory frameworks, and cultural attitudes toward sustainability. Fostering collaboration and innovation between nations will be key to achieving a more sustainable future. By learning from each other’s experiences and fostering a culture of innovation, China and Switzerland can lead the way in creating resilient urban environments that serve both current and future generations. The journey toward sustainability is a collective effort requiring the commitment and collaboration of governments, industries, and communities alike.

Article posted on May 1, 2025.

Author

Local Lead Expert of the Sino-Swiss Zero-Emission-Building (ZEB) Project and registered Architect SIA/ETH in Switzerland

Yin Li holds a Bachelor's degree in Architecture from Zhejiang University and a Master's degree at ETH Zurich. After graduating, he worked for eight years at Giuliani Hönger Architekten in Zurich, Switzerland, during which he also obtained an MAS Master of Advanced Study in Building Energy Engineering from Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts (HSLU). In 2022, he returned to China to continue his work in architecture and consulting as the specially appointed local lead expert for the Sino-Swiss ZEB Project. He has engaged in architectural practice in various locations, led architectural design competitions in Shenzhen and Switzerland, and is frequently invited to participate in teaching practices and guest lectures at several universities.