December 7, by Felicia Wang, Startup Manager at Swissnex in China, and Kai Kim, Lawyer at Taylor Wessing law firm

Q: What are China’s CBDT and PIPL?

The PIPL refers to China’s Personal Information Protection Law, which came into effect in November 2021. The PIPL is often called China’s GDPR, as it resembles Europe’s General Data Privacy Regulation. From a Chinese perspective, however, the PIPL is only one of several pieces in China’s larger data framework. This framework also contains, among others, China’s Data Security Law and China’s Cybersecurity Law, both of which came out years before the PIPL.

China’s CBDT refers to China’s legal regime on the cross-border transfer of data. This means the export of data from China to overseas. In that sense, China’s CBDT control regime has wider coverage than the PIPL, as it not only deals with the export of personal information but also other categories of data, such as “important data”.

Q: What impact does it have on foreign startups?

Foreign startups are impacted by the PIPL and China’s CBDT in various ways.

Firstly, while the PIPL does in many regards resemble legislations such as the GDPR or the Swiss Federal Data Protection Act, it also includes a variety of requirements that exceed those familiar to foreign startups. To name one example: China’s data privacy rules not only require explicit consent for the handling of personal information, but require separate and additional consent under specific circumstances, for example when personal information is considered sensitive, or when personal information shall be exported abroad.

Secondly, as mentioned above, the PIPL only forms one of several pieces of China’s data framework. As a result, China’s data regime not only focuses on data privacy, but also extensively on national security concerns. This creates additional scrutiny for foreign startups handling data in or from China.

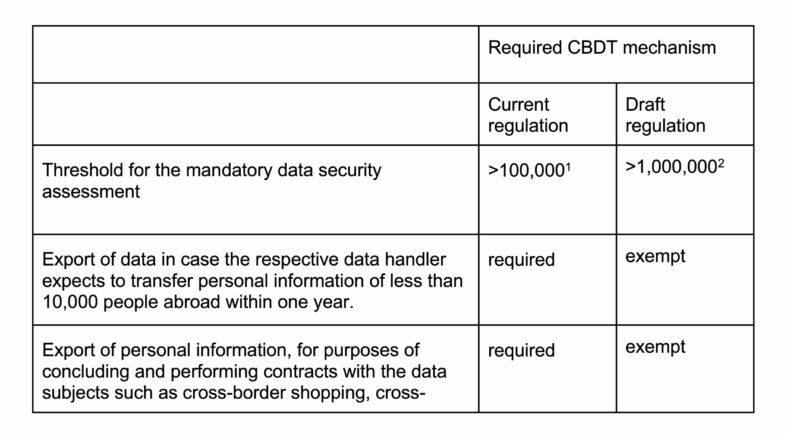

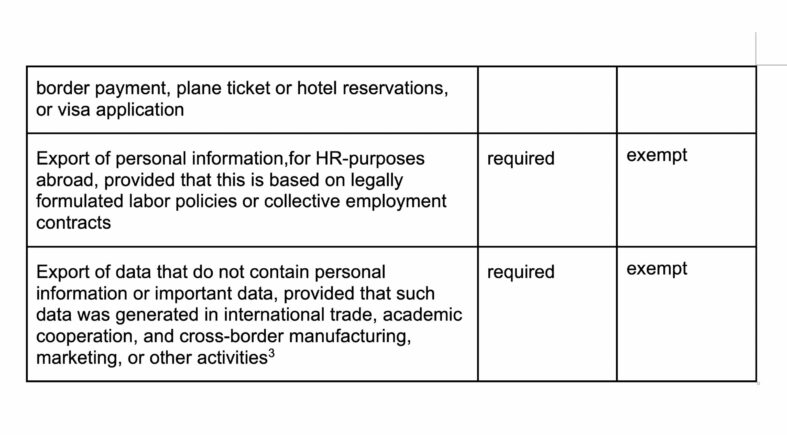

Thirdly, when it comes to the CBDT regime, the biggest difficulty for foreign startups is often determining and conducting the correct mechanism for a legal export of data from China. Under China’s data regime, there are generally three possible mechanisms that may form the legal basis for the export of data from China to overseas:

- a mandatory data security assessment with the competent local cybersecurity and informatization department;

- the conclusion and filing of a standard contract between the data handler in China and the recipient abroad or

- obtaining a personal information protection certification issued by a specialized third-party agency.

Q: What kind of difficulties does it pose for foreign startups?

The first difficulty that foreign startups often face in this regard, is determining the correct mechanism for the data possessed by them. A data security assessment, for example, will be mandatory if the data handled by a foreign startup is considered “important”. Unlike personal information, however, identifying important data is quite complicated and not always fully clear, which creates a lot of uncertainty for foreign startups.

The second difficulty will then be to conduct the correct mechanism in the right way and in due time. For the completion of data security assessments, for example, the deadline has expired in February 2023, while for the conclusion and filing of standard contracts, the deadline just expired at the end of November 2023.

Q: what has been changed in the new draft regulations on CBDT?

The Draft Provisions suggested welcome exemptions from the above-mentioned CBDT mechanisms, as well as some certainty with respect to what may be considered as important data. On the other hand, all other statutory obligations under the PIPL would continue to apply (e.g., securing consent from the data subject upfront, and preparing a transfer impact assessment report). Given the draft status of the Draft Provisions, however, these changes are not yet applicable. When the Draft Provisions will be finalized and whether the final version will contain the same changes as the Draft Provisions from the end of September are not yet clear.

Some of the main changes by the Draft Provisions are as follows: